Although it’s a superhero story in prose, the Wild Cards saga begins with nothing less than alien first-contact. In 1946, Tachyon lands on earth alone, desperate to stop the release of a gene-altering virus engineered by his family on the planet Takis. His failure allows the virus to fall into the hands of a pulp-worthy villain who carries it high above New York City. There, in a desperate and heart-stopping sky battle worthy of the best WWII flick, Jetboy attempts to stop the release of the alien biological toxin. The young fighter pilot gives his life in the attempt, but the virus is released in a fiery explosion six miles up, floating down to the city below and carried across the globe in the upper atmosphere’s winds. On that day in NYC, 10,000 people die.

The effects of the virus are immediate and devastating, exactly as its alien creators envisioned. Each person transformed by the virus responds in a completely unpredictable manner. What can be predicted, though, are the numbers: 90% of those affected will die horrifically, 9% are hideously transformed, and 1% gain spectacular powers. The arbitrary nature of the individual outcomes lead first-responders to nickname the virus the Wild Card, a metaphor applied to the victims as well. The majority who die draw the Black Queen; those who manifest the gruesome side effects are cruelly labeled Jokers; and the few graced with enviable powers are elevated to the designation Ace. Even the “natural” and unaffected themselves will bear the label “nats.”

The history of humankind changes on September 15, 1946, ever after known as Wild Card Day. This first installment in the Wild Card series covers the event and its aftermath, exploring the historical, social, and personal impact of that day. Although some of the action occurs on the West Coast, in D.C., and abroad, most of the events center on NYC. Each story recounts the experience of a nat, a joker, an ace, or the lone resident alien, beginning in 1946 and ending in 1986.

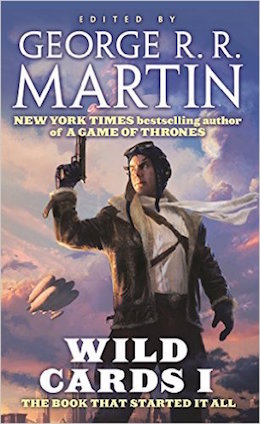

Like other shared world books, writing Wild Cards involved multiple authors. Each wrote their own chapter about a major character of their creation, interwoven into a world populated with figures imagined by the other authors. The chapters are broken up by interstitial shorts, most of which were written by editor George RR Martin. The book’s timeline ends in the year it was actually written in Real Life (1986; it was published in 1987), although three new chapters appear in the expanded edition released in 2010 by Tor.

For a book compiled from segments written by fourteen different authors, Wild Cards is remarkably consistent in its tone and thematic unity. While stylistic differences in the writing are clear, they are in no way jarring. The interludes further the world-building and add depth to the book’s tonal range, whether through the first-person oral histories of the Army men scrambling to deal with Tachyon’s landing, or the convulsive headtrip of Hunter S. Thompson in Jokertown. The shared topography grounds the plot and characters in a lived environment, especially the richly-developed NYC with its landscape of diners, Jokertown clubs, and monuments to Jetboy. Strikingly, for a tale that demonstrates historical and social change over four decades, it remains decidedly character-driven.

There’s a lot to love about this book. From the get-go, it is relentless, with the first several chapters a non-stop, heart-wrenching, chill-inducing kick to the face (featuring Jetboy, the Sleeper, Goldenboy, and Tachyon). In the following stories and eras, we’re introduced to characters that will continue to populate the series for many books to come.

Time’s Passage

For readers interested in investigating the past, the sense of history permeating Wild Cards is one of its most remarkable and consistent features. The book provides a longue durée view of a world changed forever by a single event, with the results rippling onwards through time. Our jokers and aces populate a United States rocked by social and political upheaval, dealing with issues that continue to be timely: police violence, persecution of minorities, violent protests, class conflict, government failure, and the scarring legacy of war.

Wild Card history begins in a post-WWII USA, but the spirit of each successive era suffuses the tale. The virus is released into cities filled with veterans, families hollowed by lost sons, children trained in air raid drills. Later, the crippling fear of blacklists ratchets up the tension in “Witness,” with the Red Scare and the Cold War that follows. The day that JFK died, so memorable for those who lived through it, becomes the day that ultimately births the Great and Powerful Turtle. The heady activism of the ’60s, with its demonstrations and idealism, give way to excesses of the’70s. The jokers’ fight for civil rights fairly catapults from the page. The book ends in the gritty 1980s, with Sonic Youth even making an appearance at CBGBs. As alternate-history, Wild Cards humanizes each of these crucial periods in U.S. history through the experiences of individual jokers, aces, and nats.

Historical popular culture is a presence as well. The entire story begins in 1946, after all, with a crashed spaceship and an alien in New Mexico. Tachyon may not look like a little green spaceman, but he ties traditional science fiction to the flyboy fandom of WWII war comics. The Turtle’s buddy-story with Joey brings to life the comic-collecting nerds of the 1960s’ Silver Age. The James Bond spy secrecy of the Cold War appear in “Powers,” whereas The Godfather and representations of the Mafia underlie Rosemary and Bagabond’s story. Wild Cards is authentic alt-history, but is also self-aware and self-reflexive in its shout-outs to the pop culture of its various time periods.

Class War and Persecution in Jokertown

On the surface a story about monsters and superheroes, Wild Cards is first and foremost a story about people; sadly, the jokers are treated in a way practically lifted from recent headlines. They are the most vulnerable population in the Wild Cards world, victimized and exoticized; for safety’s sake they live together in the Bowery district. Yet, even there they are beaten by police and are drafted into Vietnam in disproportionate numbers, the ultimate “cannon fodder.” They’re a population plagued by depression and suicide, until their anger finally explodes into violence and the Jokertown Riots. All our own past failings as a society come to the fore in the plight of the jokers, an eminently recognizable echo of real life. The jokers provide the dark mirror that reflects our failings back at us.

While jokers and their experience touch on the long history of persecution and civil rights in the U.S., one social area that Wild Cards does not so successfully represent is the women’s movement. The book exhibits limited roles for women and rather unbalanced gender dynamics; one wonders how the new powers brought by the virus might have impacted the history of feminism and the experience of women. What would have happened, for example, if Puppetman were a woman?

We Can Be Heroes? Even Jokers?

Such a world needs heroes most of all. Martin and his crew of contributors developed the Wild Cards universe in the mid-’80s when the superhero genre was undergoing dramatic transformations. Together with Watchmen (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987), Wild Cards portrayed comic book heroes in a newly seedy, dark, and cynical manner. It makes sense, then, that a pervasive theme of Wild Cards is the exploration of heroism in all its forms.

Time and again the wild cards universe shines a light on what it means to be a hero, even deconstructing the notion altogether. The very structure of the book allows for the contrast of heroic figures one after another. It all begins with Jetboy, the war hero and fighter pilot, who survived the battles of WWII to finally die in mortal combat in an effort to protect the fates of all. Jetboy was the last great nat hero, before his only failure ushered in the new era of the wild card.

Jetboy as the last hero of the old world is immediately contrasted with the first wild card hero, introduced in the next chapter. Croyd Crenson, the boy Sleeper, draws a reinfection by the virus every time he sleeps, shifting through new physical manifestations and powers, man to lizard and everything in between. Croyd does not fit the hero’s mold so flashily embodied by Jetboy. Frequently he’s monstrous; he becomes a drug addict; he’s a thief and a crook. But we find that his thieving supports his siblings and incapacitated parent; amphetamines allow him to patrol the Bowery’s streets to protect its vulnerable population from joker-bashers. Living in constant fear of drawing the Black Queen every time he sleeps, perhaps Croyd’s faults can be forgiven, since he relives Wild Card Day each time he wakes. Thanks to his many transformations, though, Croyd becomes both joker and ace. Even when his mind later becomes unhinged, Croyd remains a striking figure as the first hero of jokers.

Jetboy and Croyd find their opposite with the subsequent chapter, that of the first wild card villain, Goldenboy. Everything about him seems heroic, but his fatal flaw leads to an irreversible decision. As an easy-going kid with good looks, super strength, and a literal golden halo surrounding him, he becomes a member of the Four Aces, fighting for democracy and all that’s good in the world. In segregated 1947, his best friend is Tuskegee airman Earl Sanderson, himself a hero in the early civil rights movement. But whereas Earl fought for every privilege in a country entrenched in racial inequality, Goldenboy had every opportunity handed to him. As a handsome, young, white, and invincible hero, his life was one of ease, both before and after Wild Card Day. The cracks in his hero façade become evident as his success grows: he is a womanizer, a profligate spender, and ultimately proves himself incapable of standing up for what is right. His greatest and most important battle comes not in the field, against coups or enemy forces. It comes instead on safe home soil, in a civilized government building, surrounded by the powers of democracy for which he ostensibly fought. His testimony as a “friendly witness” in front of Congress reveals that, when truly powerless and afraid, Goldenboy is not a hero, but a villain: the Judas Ace.

The Wild Card authors return again and again to what it means to be a villain, or a hero, with Puppetman and Succubus, with Fortunato and Brennan, etc. The Turtle explicitly lays out why it matters, even when powerless:

“If you fail, you fail,” he said. “And if you don’t try, you fail, too, so what the fuck difference does it make? Jetboy failed, but at least he tried. He wasn’t an ace, he wasn’t a goddamned Takisian, he was just a guy with a jet, but he did what he could.”

The structural circle of heroism comes together at the end of the book with a nat, Brennan, the focus of the story once again. This time, a nat character finds himself surrounded by more powerful jokers and aces. He tries, like Jetboy—but this time, he wins.

Powers: “I’m not a joker, I’m an ace!”

Another unending source of delight and horror within the Wild Cards universe can be found in the powers manifested by those that the virus changes. The advantage of working with multiple authors reveals itself in the real diversity of wild cards drawn by the characters. The virus is infinitely flexible by its very nature, with the result that the authors are able to stretch their creativity. Some of the powers are fairly standard, such as the ability to fly, read people’s minds, or walk through walls. But most of the powers are paired with a handicap: the Turtle’s incredible telekinesis only works when he is hidden from sight within his armored, floating shell; all the various animals of New York City attend to their protectress Bagabond, who herself struggles to interact with humans and lives homeless on the streets; Stopwatch halts time for 11 minutes, but ages significantly when he does so.

It is the joker manifestations that truly add heart to the story, however, bringing a formidable pathos to the world. Many others changed by the virus exhibit physical deformities or illness. The jokers are our wounded and injured—the scarred, the disabled, the sick, those living with chronic pain and emotional despair. Even for the beautiful Angelface, the slightest touch bruises the flesh and her feet are continuously black and blue. Society treats these figures with disdain and cruelty; they are brutalized, their rights ignored, and until Tachyon opens his Jokertown clinic, they are even unheeded and shunned by the medical establishment. In the aftermath of Wild Card Day, these are the people that fell through the cracks, those who lost their voice in a world that would rather pretend that their pain does not exist. Rather than the feted aces with their superhero powers drinking cocktails at Aces High, it is the horrific treatment of jokers that makes Wild Cards feel so disturbingly real.

With this first volume, the Wild Cards series gets off to a stupendous start. This initial entry sets the stage for what’s to come in the later books, providing background to the virus and the historical and social changes it caused. Wild Cards is immeasurably enriched by the various authors who bring it a multiplicity of viewpoints and ideas, all expertly wrangled by the editor. In the end, the book’s greatest strength (and what made it stand out in 1987) is that it represents a variety of eras and a multitude of voices: ace, joker, nat.

Katie Rask is an assistant professor of archaeology and classics at Duquesne University. She’s excavated in Greece and Italy for over 15 years.